The Übermensch

Nietzsche, Raskolnikov, and Jedis

This is a response to Scott Alexander’s piece on Nietzsche’s master-slave morality.

Scott,

I’m not big on ethics, but if I was, master morality sounds pretty good to me. I mean, if being jacked, virile, and rich isn’t “good,” what is? Do I even want to be good?

But an overlooked danger of master-slave morality is what I’ll call the Raskolnikov Effect. Let’s look at one of Nietzsche’s übermensch:

Alcibiades was good at basically everything. He was renowned for military victories at Cyzicus and Abydos, and when his strategies failed, he simply changed teams. Athens, Sparta, and Persia were all his side-chicks. So was the Queen of Sparta.

He was cultured and brilliant, sponsoring symposia and hanging out with Socrates. Even Plato paid his respects, writing Alcibiades I and Alcibiades II.

The problem is, you’re not Alcibiades. You’re a gruel-eating peasant.

You don’t win glory—you beg for rain. Hippolyta, meaning “freer of horses,” left you for Eukles, who has a bigger mud hut.

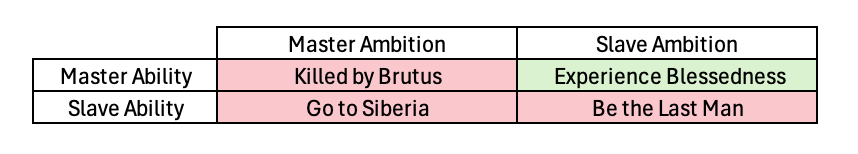

It seems you have two roads forward:

…

Become Alcibiades

Let’s say you have the nature, nurture, and luck of an übermensch. Tough formula to get right, but you nailed it. Scott writes:

So you’re Caesar, you’re an amazing general, and you totally wipe the floor with the Gauls. You’re a glorious military genius and will be celebrated forever in song. So . . . what? Is beating other people an end in itself? […] Also, if you defeat the Gallic armies enough times, you might find yourself ruling Gaul and making decisions about its future. Don’t you need some kind of lodestar beyond “I really like beating people”? Doesn’t that have to be something about leaving the world a better place than you found it?

No, Scott, you really don’t. Some people love their job. This is the happy ending.

However, there is one issue: everyone hates you. The good news is, when you’re far above the masses, you tend to disregard their opinions. The bad news is, their opinions don’t disregard you.

…

Flip the script

This is what Nietzsche feared. He speculates that our obsession with slave morals like humility and frugality began with the Jews, who were persecuted by literally everyone. Then Christ rose, Rome fell, and a few hundred years later gruel-eaters are worshipping people who renounce fortunes to walk barefoot and kiss lepers.

Eventually, he warns, the West will deteriorate to the Last Man, a creature antithetical to Alcibiades and pretty much every life form ever. He is content with trivial pleasure, avoids all challenges, and hides his oozing envy by sucking off mediocrity. I have a lot to say about these types, but I’ll save it for an addendum.

But there’s one more . . .

…

Spiral the fuck out.

We tend to think of ourselves as the chosen ones. No one wants to be a stormtrooper or a muggle if Jedis and wizards exist. But reality is brutal:

I’m Alcibiades. But I’m eating gruel. But I’m Alcibiades.

The brain cannot reconcile the two. But it doesn’t know that; it oscillates between self-justification and reality until . . . System Error. Wrrrrrrrr

This is what drove Raskolnikov mad. The smells of St. Petersburg, the oppressive ceilings, dreams of Napoleon, but the guilt of a commoner. Dostoyevsky cleanses him with the epitome of slave morality: eight years in Siberia and the love of Sonya, a pious prostitute.

…

I spent a lot of time in this spiral. And when I got out, I realized the other two weren’t viable either. In fact, I’m certain they’re the same option.

It’s absurd that domination can be separated from ressentiment. I’m not sure if this is Nietzsche or Scott’s framing, but it didn’t take a second—let alone hundreds of years—between Bronze Age übermensch like Achilles shitting on everyone and a gruel-eater waking up and thinking: Huh, what if we were the good guys and the nobles were the bad ones? Hmmmmmm . . .

I reject both sides of the coin. As with all things, there is a du, and we must moderate ourselves accordingly. As Zhuangzi writes, “we cultivate our spirit by accepting what is necessary and inevitable—to be what we can’t help being. How can there be any difficulty in that?”

We should stop blocking out the good things coming into our lives. And living out our lifespan in blessedness is a pretty good proxy for this:

By maximizing effort and minimizing expectations—increasing the surface area of luck—we are actualized.