Plato II

Death of Socrates

FOREWORD

This is the second of the Plato series. I will be using the G. M. A. Grube translation of the following chapters:

Meno

Phaedo

Both stories, relative to the trial of Socrates, are more focused on the Forms. Meno touches on the nature of virtue and knowledge with the questioning of the slave boy. On the other hand, Phaedo covers his final hours and zooms in on the immortal soul.

.

.

.

MENO

[ This is not part of his trial. Meno just a rich guy. ]

Meno: “Can virtue be taught? Is it something innate or gained by practice?”

Socrates: “Hold up, Meno. What even is virtue? Can you define it?”

Meno: “Sure. Virtue is different for everyone—a man's virtue is managing public affairs, a woman's is managing the home, and so on.”

Socrates: “That's just a list of virtues, not a definition. What is the common denominator in all these virtues?”

Meno: “I can’t think a thing in common.”

Socrates: “Meno, is virtue one thing or many? Like how roundness is a shape but not the only shape?”

Meno: “Virtue is many things: justice, courage, wisdom, and more.”

Socrates: “But they all share something that makes them virtues, right? Like how all shapes share ‘shape-ness’. What is that common thing in virtue?”

Meno: “Virtue is desiring good things and having the power to get them.”

Socrates: “Does anyone desire bad things, knowing they are bad? If they know bad things harm them, do they still desire them?”

Meno: “They desire what they think is good, but it might actually be bad.”

Socrates: “Then everyone desires good things. If virtue is desiring good things and acquiring them, it's really about being able to secure these goods, right?”

Meno: “Yes, that’s what I meant.”

Socrates: “But what if someone acquires these goods unjustly? Is that still virtue?”

Meno: “No, that would be wickedness.”

Socrates: “So, virtue must include justice, moderation, or piety. Simply acquiring goods isn't virtue; how you acquire them matters.”

Meno: “I agree, it must be done with justice to be virtue.”

Socrates: “You said virtue is securing good things with justice, but justice is just a part of virtue. You're still not telling me what virtue as a whole is.”

Meno: “I don't think one can know a part of virtue without knowing the whole.”

Socrates: “Exactly. So, tell me again, what is virtue?”

Meno: “Socrates, you're like a torpedo fish, numbing me. I used to think I knew what virtue was, but now I’m completely perplexed.”

Socrates: “The torpedo fish numbs others because it’s numb itself; if I numb others, it's because I don't know the answers either.”

Meno: “But how will you search for something when you don’t know what it is? How will you recognize it if you find it?”

Socrates: “Ah, you're bringing up a debater’s argument: If you know what you're searching for, you don't need to search, and if you don't know it, you won’t recognize it when you find it.”

Meno: “Isn’t that argument sound?”

Socrates: “Not to me. I've heard wise men and women talk about divine matters.”

Meno: “What did they say?”

Socrates: “What was both true and beautiful.”

Meno: “What was it, and who were they?”

Socrates: “The speakers were priests and priestesses who account for their practices. Pindar and other poets say this too: The human soul is immortal. It dies and is reborn, but never destroyed, so one must live piously.”

“Since it is immortal and has seen all things, there is nothing it hasn’t learned. It can recollect things it knew before, like virtue. Since all nature is related, nothing prevents a man, by recalling one thing, from discovering everything else.”

“Searching and learning are recollection. We shouldn’t believe that debater’s argument; it would make us idle, whereas my argument encourages us to search.”

Meno: "What do you mean we don’t learn, but rather recollect? Can you show me?"

Socrates: "Call one of your attendants."

[ Meno calls his slave. ]

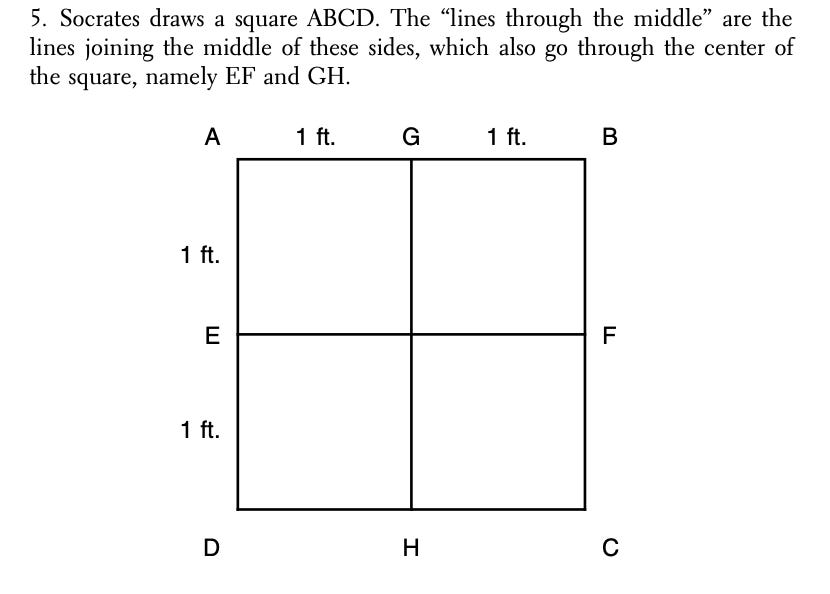

Socrates: “Do you know what a square is? It has four equal sides, right?”

Boy: “Yes.”

Socrates: “And it has lines through the middle that are equal too? And such a figure could be larger or smaller?”

Boy: “Yes.”

Socrates: “If it were two feet by one foot, the figure would be two feet?”

Boy: "Yes."

Socrates: “Now, imagine one twice the size. How many [square] feet will that be?”

Boy: “Eight.”

Socrates: "Now, how long will each side of this larger square be?”

Boy: “It will be twice as long, obviously.”

Socrates: “You see, Meno, I'm not teaching the boy anything; I'm just questioning him. But does is he right?”

Meno: “Certainly not.”

Socrates: “Now watch him recollect Boy, do you still believe that a figure double in size is based on a line double the length?”

Boy: “I do.”

Socrates: “Let's draw the square. How big is it?”

Boy: “Four times as big.”

Socrates: “So a figure based on a line twice the length is four times as big?”

Boy: “Yes.”

Socrates: “Now, on what length should the eight [square] foot figure be based?”

Boy: “Three feet.”

Socrates: “Let's see. If it's three feet by three feet, how big is the square?”

Boy: “Nine [square] feet.”

Socrates: “But the double square was supposed to be eight [square] feet, right?”

Boy: “Yes.”

Socrates: “But then on how long a line?”

Boy: “By Zeus, Socrates, I don't know.”

[ Socrates turns to Meno ]

Socrates: “You see, Meno, he thought he knew but now realizes he doesn't. Have we done him harm by making him perplexed?”

Meno: “I don't think so.”

Socrates: “He's now more eager to learn, whereas before he thought he knew.”

Meno: “So it seems.”

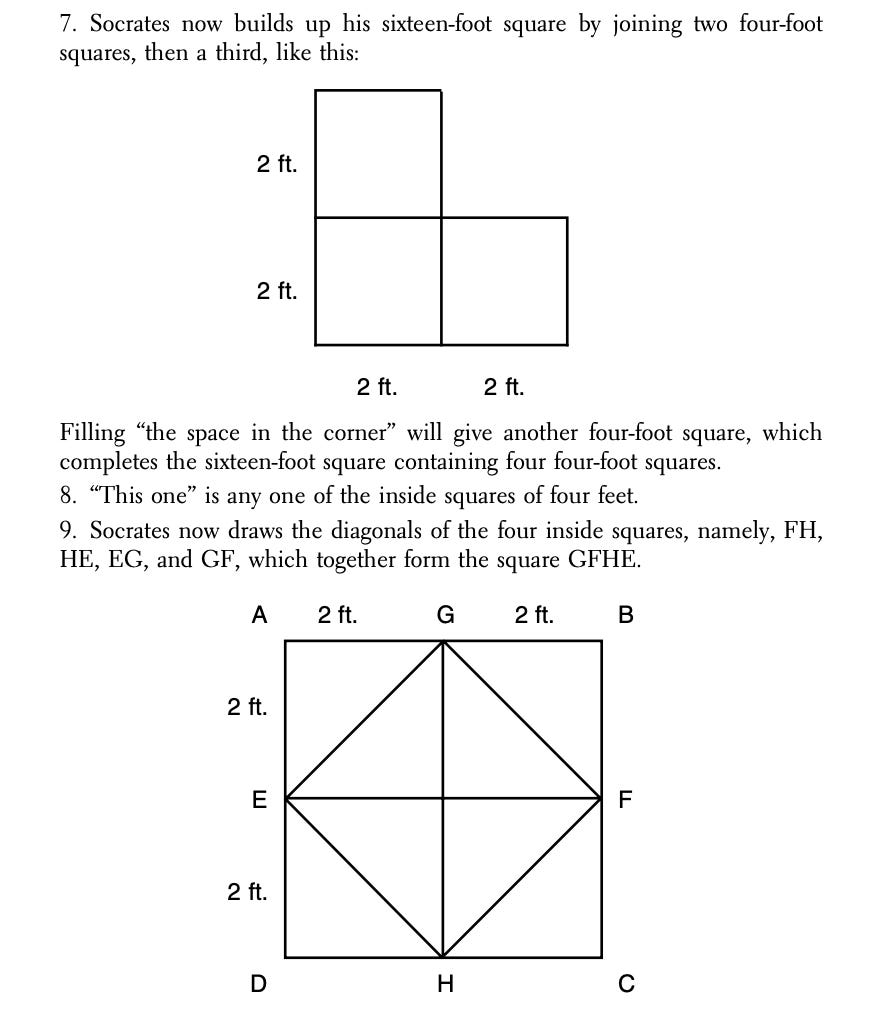

[ Socrates turns back and draws some diagonals ]

Socrates: “Each line cuts off half of each figure, right?”

Boy: “Yes.”

Socrates: “How many of this size are there in this figure? And in this other one?”

Boy: “Four. And the other has two”

Socrates: “And how many feet does this make?”

Boy: “Eight.”

Socrates: “Based on what line?”

Boy: “This one.”

Socrates: “Which is the diagonal of the square?”

Boy: “Yes. The double figure is based on the diagonal.”

[ Socrates dismisses the boy and turns back to Meno ]

Socrates: “Were these answers his own?”

Meno: “Yes, they were.”

Socrates: “So, a man has true opinions within him about things he doesn't know?”

Meno: “It seems so.”

Socrates: "If he always had it, he would always have known. If he acquired it, it couldn't have been in this life. Then he learned them at some other time?"

Meno: “It seems so.”

Socrates: “If the truth is always in our soul, the soul must be immortal. We should always try to seek out and recollect what we don't know.”

Meno: “I think you're right, Socrates. But is virtue is teachable or not?”

Socrates: “I usually like to investigate what virtue is first. But let’s proceed with a hypothesis: If virtue is knowledge, it can be taught; if not, it can't be.”

Meno: “Ok, sounds good”

Socrates: “Let's agree that virtue is something good. If there's nothing good outside of knowledge, then virtue must be a kind of knowledge.”

Meno: “That makes sense.”

Socrates: “Virtue makes us good, right? Therefore, virtue is something beneficial?”

Meno: “That follows.”

Socrates: “Now, what things benefit us? Health, wealth, and so on. But these can also harm us if used improperly, right?”

Meno: “Certainly.”

Socrates: “So, it's the right use of these things that benefits us, and the wrong use that harms us?”

Meno: “Yes.”

Socrates: “So, virtue, being beneficial, must be a form of knowledge since all the qualities of the soul are beneficial when directed by wisdom.”

Meno: "Yes, I agree.”

Socrates: “So, the good aren’t naturally good; they must learn it.”

Meno: "Yes, it must be learned."

Socrates: "But is virtue actually teachable?"

Meno: “It seemed right at first, but do you doubt it now?”

Socrates: “If something can be taught, there must be teachers, right? But I can't find anyone who truly teaches virtue. Let’s ask Anytus.”

Meno: "Good idea."

Socrates: “Anytus, who would we send someone to if they wanted to learn medicine? To a physician?”

Anytus: “Of course.”

Socrates: “So if Meno wants to learn virtue, should we send him to those who claim to teach it, like the sophists?”

Anytus: “No, the sophists ruin and corrupt people.”

Socrates: “Well, if not the sophists, where should Meno should go to learn virtue?”

Anytus: “Any Athenian gentleman can teach him better than the sophists.”

Socrates: “Do these gentlemen become virtuous without learning from anyone? Can they teach what they haven't learned?”

Anytus: “They learned from gentlemen before them.”

Socrates: “But can they teach virtue? Consider Themistocles, a great man. He taught his son many skills, but no one claims his son was as virtuous as him. If virtue could be taught, wouldn’t he have taught it to his son?”

[ Anytus gets angry because he thinks Socrates is slandering Themistocles and himself ]

Socrates (to Meno): “How about those who offer themselves as teachers of virtue?”

Meno: “Sometimes they say virtue can be taught, other times not.”

Socrates: “Can they be teachers if they can’t agree on whether it can be taught? I can’t name any subject where those who claim to teach it are not recognized as teachers and are even thought to be poor in the subject they profess to teach.”

Meno: “I don't think so.”

Socrates: “If neither the sophists nor the ‘worthy’ men are teachers of virtue, then there are no teachers, and therefore, no learners. We agreed that without teachers or learners, a subject can't be taught. So, virtue can't be taught.”

Meno: “It seems so, but then how do good men come to be?”

Socrates: “Maybe success doesn't always come from knowledge alone. Consider: if someone knows the way to a place, they can guide others correctly. But if someone merely has a correct opinion about the way, they can guide just as well.”

Meno: “True opinion is just as effective as knowledge?”

Socrates: “But true opinions are like untied statues—they don't stay put unless ‘tied down’ by understanding the reasons behind them. Once tied down, they become knowledge, which is why knowledge is more valuable.”

Socrates: “Since virtue is a good thing and must involve correct guidance, it seems that either could make a person virtuous. But since virtue doesn't appear to be teachable, it might more akin to true opinion.”

Meno: “That makes sense.”

Socrates: “If statesmen don’t guide through knowledge they must guide through true opinion. This makes them similar to soothsayers and prophets, so we consider them similarly divine?”

Meno: “Yes, and it seems appropriate, though Anytus disagrees.”

Socrates: “It seems virtue is neither innate nor teachable. Instead, it is a divine gift, unaccompanied by understanding. Unless there is a statesman who can teach others to be statesmen, those with virtue are like shadows compared to someone who truly possesses knowledge.”

Meno: “That’s a fitting analogy, Socrates.”

Socrates: “However, to truly understand how it comes to be in men, we must understand what it is. But now, I must go.”

Wisp’s Note: So the difficulty I have with this is that he isn’t teaching the child. I really think questioning is teaching when breaking down complex problems into easily digestible pieces.

.

.

.

PHAEDO

[ Phaedo is recounting Socrates’ final hours to a group of Pythagoreans. ]

[ Unlike Crito and Apology, Phaedo incorporates more of Plato's own philosophical ideas, particularly the theory of eternal Forms. ]

Echecrates: “What was the conversation about?”

Phaedo: “On the day of his death, we arrived early. When we entered, Socrates had just been released from his chains. His wife, Xanthippe, was crying, holding their baby. Socrates asked Crito to take her home.

[ Scene changes ]

Socrates (rubbing his leg): “It's strange how pleasure and pain are connected. If you chase one, the other follows. If Aesop noticed, he’d write a fable about how they got connected as punishment.”

…

Cebes: “How can it be wrong to take one’s own life, but right for a philosopher to be willing to die?”

Socrates: “The gods are our guardians, and we are their possessions. Would you be angry if one of your possessions killed itself without your consent?”

Cebes: “Yes, I would. But why be eager to die if the gods are good masters?”

Socrates (looking pleased): “I should make my case. I believe I'm going to wise and good gods, and the afterlife is better for the good than the wicked.”

“Moreover, someone who has devoted his life to philosophy should face death with confidence, hoping for the greatest blessings after death. If our entire lives are a preparation for death, it would be absurd to resent it when it finally arrives.”

Simmias (laughing): “Most people would say philosophers are nearly dead already and deserve to be.”

Socrates: “They might be right, but they don't understand what true philosophers are and what kind of death they deserve. Do we agree that death is the separation of the soul from the body?”

Cebes: “Yes, that’s what death is.”

Socrates: “Then, would a philosopher value pleasures like food, drink, or sex?”

Cebes: “No, not at all.”

Socrates: “Exactly. A philosopher focuses on the soul and tries to distance it from the body as much as possible, right?”

Cebes: “Yes.”

Socrates: “The majority might think that someone who doesn’t care for bodily pleasures is close to death. What do you think?”

Cebes: “That’s certainly true.”

Socrates: “And when it comes to gaining knowledge, isn’t the body an obstacle? Don’t we find that our senses—sight, hearing—often deceive us?”

Cebes: “Yes, that’s true.”

Socrates: “So, if we want to understand absolute goodness, justice, and beauty, we must do so through pure thought, untainted by the body, right?”

Simmias: “Indeed.”

Socrates: “We must separate the soul from the body, and thus I hope to achieve wisdom in death. True philosophers prepare for death by beginning in life.”

“True virtue comes from wisdom, which brings courage, moderation, and justice. Those who practice philosophy correctly are like Bacchants, few in number but truly initiated.”

Cebes: “Socrates, many deny that the soul continues after death. They think it dissolves like smoke. How do you answer them?”

Socrates: “If the souls of the dead come back to life, they must exist somewhere after death. If not, we need another explanation.”

Cebes: “That makes sense.”

Socrates: “Consider all things. Large comes from small and weak from strong. So, life and death must come from each other.”

“If the processes of becoming didn’t balance each other, like waking up after sleeping, everything would eventually stop becoming and stay in one state. Thus, if we can die, we can also go from death to life. And so the soul exists after death.”

Cebes: “Ok, that checks out.”

Socrates: “Moreover, if learning is recollection, as we often say, then our souls must have existed before we were born. How else could we recollect things?”

Simmias: “What’s the proof of this again? Remind me.”

Cebes: “When someone is questioned properly, they give the right answers, showing they must have already known it.”

Socrates: “Let’s take a simple example. Seeing one thing can make you think of something else, like seeing a lyre reminding you of the person who owns it. This is recollection. We recognize Equality not just from seeing equal sticks or stones but from knowing the Equal itself, which is different from those things.”

Cebes: “Yes.”

Socrates: “Then, if the realities like the Equal exist, so must our souls. Both must exist if we are to have any knowledge.”

Cebes: “What if the soul scatters like a breath when we die, like people say?”

Socrates: “We should ask what kind of thing is likely to be scattered. Is it something composite and changeable, or something simple and unchanging?

Cebes: “The former.”

Socrates: “So, things like the Equal and the Beautiful, which are unchanging, cannot be scattered. But physical objects, which are always changing, can be.”

Cebes: “That seems true.”

Socrates: “The body belongs to the changing, visible world, but the soul is more akin to the invisible, unchanging realm. Thus the soul is indissoluble, while the body, being composite, is prone to dissolution.”

Cebes: “Agreed.”

Socrates: “If the soul is pure when it leaves the body, it will go to a place like itself, the divine and immortal realm. If the soul is impure, attached to physical pleasures, it will be drawn back to the physical world and may even wander as a ghost.”

“Impure souls might even be reincarnated into animals or creatures that match their character in life like donkeys or wolves, while those who practiced virtue without philosophy might be reborn into gentle creatures like bees, ants, or moderate humans.”

“Only those who practice philosophy and are completely pure when they die can join the divine. True philosophers avoid bodily pleasures not out of fear of poverty or dishonor but because they care for their soul.”

Simmias “This is convincing, but what if the soul is like a harmony that arises from the proper arrangement of the body?”

Cebes: “Also, the soul may be stronger than the body, but that doesn’t mean it lasts forever. It's like saying an old weaver is safe because his last cloak is still intact, even though he outlasted many cloaks before it.”

Socrates: “Simmias, if the soul is a harmony, we must ask if it could exist before the elements of the body were arranged in harmony, or if it could act contrary to those elements once it was composed.”

Simmias: “No, Socrates, it could not. A harmony cannot exist before the elements that compose it, and it cannot act independently of them.”

Socrates: “Exactly, this creates a contradiction. If the soul is a harmony, it could not have existed before the body, but the soul existed before our birth.”

“Furthermore, the soul would not be able to oppose the body's desires and actions. Yet, it often resists the body's impulses, guiding it toward reason and discipline.”

Simmias: “Indeed, it seems more divine, ruling over rather than ruled by the body.”

Socrates: “Cebes, when I was young, I tried pursuing natural science to understand why things happen. But I realized that physical explanations like heat and cold were not enough.”

“The true cause isn’t just physical; it’s the reasoning behind it. Just like I’m sitting here because I chose to stay in Athens, not just because of my bones and sinews.”

“The physical aspects are necessary but not the true cause. Some may claim that the world is held together by physical forces like a vortex or air, but they miss the real reason, which is the best and most just arrangement by the divine.”

“So, regarding the soul’s immortality: If the soul is connected to eternal truths like the good and the just, it’s not something that can be destroyed like a physical object. The soul’s nature aligns with eternal concepts, suggesting it’s eternal too.”

Cebes: “What, then, do you consider the true cause?”

Socrates: “I believe things like the Beautiful and the Good exist in themselves. Everything that is beautiful is so because it shares in the Beautiful.”

“This applies to everything: what makes something big is Bigness, what makes something two is Twoness. These forms are the true causes.”

Cebes: I have no more doubts, Socrates. Neither does Simmias.

Socrates: Now, my friends, it's time for me to bathe and drink my poison

Crito: How should we bury you?

Socrates (laughing): Bury me any way you like, but remember, you're only burying my body, not me. Be of good cheer and bury it in whatever way you think is best.

Crito: “But, Socrates, there’s still time. Others delay until the sun has set.”

Socrates: “They do so because they think it benefits them, but I see no benefit in delaying. Let’s do this now.”

[ Socrates drinks and dies ]

Wisp’s Note: Quite fascinated with the premise that philosophy is the preparation of the soul for death by distancing ourselves from the body in life. That’s a good way of putting the One though.

…

Read more Plato. Or more Wisp.